Enid Blyton

| Enid Mary Blyton | |

|---|---|

A photograph which appeared in The Daily Telegraph |

|

| Born | Enid Mary Blyton 11 August 1897 East Dulwich, London, United Kingdom |

| Died | 28 November 1968 (aged 71) Hampstead, London, United Kingdom |

| Pen name | Mary Pollock |

| Occupation | Novelist, poet, teacher |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | British |

| Citizenship | British |

| Alma mater | Ipswich High School |

| Period | 1922–1968 |

| Genres | Adventure, Mystery, Fantasy |

| Subjects | children's literature |

| Notable work(s) | The Famous Five, Secret Seven, Noddy |

| Notable award(s) | Boys' Club of America for The Island of Adventure |

| Spouse(s) | Hugh Alexander Pollock (1924–42) Kenneth Fraser Darrell Waters (1943–67) |

| Children | Gillian Baverstock Imogen Mary Smallwood |

| Relative(s) | Carey Blyton |

|

Influences

Anna Sewell, Charles Kingsley, Louisa Mary Alcott, George MacDonald, Lewis Carroll

|

|

|

|

|

| Signature |  |

|

enidblytonsociety.co.uk |

|

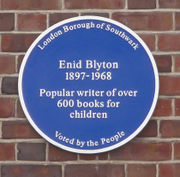

Enid Mary Blyton (11 August 1897 – 28 November 1968) was an English children's writer known as both Enid Blyton and Mary Pollock. She was one of the most successful children's storytellers of the twentieth century.

She is noted for numerous series of books based on recurring characters and designed for different age groups. Her books have enjoyed popular success in many parts of the world, and have sold over 600 million copies. Enid Blyton is the fifth most translated author worldwide: over 3544 translations of her books were available in 2007 according to UNESCO's Index Translationum.[1] she overtook Vladimir Lenin to get the fifth place behind Shakespeare.

One of Blyton's most widely known characters is Noddy, intended for early years readers. However, her main forte is the young readers' novels, where children have their own adventures with minimal adult help. In this genre, particularly popular series include the Famous Five (consisting of 21 novels, 1942–1963, based on four children and their dog), the Five Find-Outers and Dog, (15 novels, 1943–1961, where five children regularly outwit the local police) as well as the Secret Seven (15 novels, 1949–1963, a society of seven children who solve various mysteries).

Her work involves children's adventure stories, and fantasy, sometimes involving magic. Her books were and still are enormously popular throughout the Commonwealth; as translations in the former Yugoslavia, Japan; as adaptations in Arabic; and across most of the globe. Her work has been translated into nearly 90 languages.

Contents |

Personal life

Blyton was born on 11 August 1897 at 354 Lordship Lane, East Dulwich, London, England, the eldest child of Thomas Carey Blyton (1870–1920), a salesman of cutlery, and his wife, Theresa Mary Harrison (1874–1950). There were two younger brothers, Hanly (1899–1983) and Carey (1902–1976), who were born after the family had moved to the nearby suburb of Beckenham. From 1907 to 1915, Blyton was educated at St. Christopher's School in Beckenham, where she excelled at her endeavours, leaving as head girl. She enjoyed physical activities along with some academic work, but not maths.

Blyton was a talented pianist, but gave up her musical studies when she trained as a teacher at Ipswich High School.[2] She taught for five years at Bickley, Surbiton and Chessington, writing in her spare time. Her first book, Child Whispers, a collection of poems, was published in 1922. On 28 August 1924 Blyton married Major Hugh Alexander Pollock DSO (1888–1971), editor of the book department in the publishing firm of George Newnes, which published two of her books that year. The couple moved to Buckinghamshire. Eventually they moved to a house in Beaconsfield, named Green Hedges by Blyton's readers following a competition in Sunny Stories. They had two children: Gillian Mary Baverstock (15 July 1931 – 24 June 2007) and Imogen Mary Smallwood (born 27 October 1935).

In the mid-1930s Blyton experienced a spiritual crisis, but she decided against converting to Roman Catholicism from the Church of England because she had felt it was "too restricting". Although she rarely attended church services, she saw that her two daughters were baptised into the Anglican faith and went to the local Sunday School.

By 1939 her marriage to Pollock was in difficulties. In 1941 she met Kenneth Fraser Darrell Waters, a London surgeon with whom she began a friendship. After each had divorced, they married at the City of Westminster Register Office on 20 October 1943, and she subsequently changed the surname of her two daughters to Darrell Waters. Pollock remarried and had little contact with his daughters thereafter. Blyton's second marriage was very happy and, as far as her public image was concerned, she moved smoothly into her role as a devoted doctor's wife, living with him and her two daughters at Green Hedges.

Blyton's husband died in 1967. During the following months, she became increasingly ill. Afflicted by Alzheimer's disease, Blyton was moved into a nursing home three months before her death; she died at the Greenways Nursing Home, London, on 28 November 1968, aged 71 and was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium where her ashes remain. Blyton's literary output was of an estimated 800 books over roughly 40 years. Chorion Limited of London now owns and handles the intellectual properties and character brands of Blyton's Noddy and the Famous Five.

Her daughter Imogen has been quoted as saying "The truth is Enid Blyton was arrogant, insecure, pretentious, very skilled at putting difficult or unpleasant things out of her mind, and without a trace of maternal instinct. As a child, I viewed her as a rather strict authority. As an adult I pitied her." [3]

Most successful works

- The Five Find-Outers

- The Famous Five series

- The Adventure series

- The Noddy books

- The Secret Seven series

- The Malory Towers series

- The St. Clare's series

- The Wishing-Chair series

- The Magic Faraway Tree series

- The Barney Mystery series

- The Circus series

- The Mistletoes Farm series

- The Naughtiest Girl series

- The Young Adventurers Series

- The Adventurous Four Series

- The Family Series

- The Family Adventures Series

- The Secret Series

Other works

Blyton wrote hundreds of other books for young and older children: novels, story collections and some non-fiction. She also filled a large number of magazine pages, particularly the long-running Sunny Stories which were immensely popular among younger children.

An estimate puts her total book publication at around 800 titles, not including decades of magazine writing. It is said that at one point in her career she regularly produced 10,000 words a day.

Such prolific output led many to believe that some of her work was ghost-written. Yet, no ghost writers have come forward. She used a pseudonym Mary Pollock for a few titles (middle name plus first married name). The last volumes in her most famous series were published in 1963. Many books still appeared after that, but were mainly story books made up from re-cycled work.

Blyton also wrote numerous books on nature and Biblical themes. Her story The Land of Far-Beyond is a Christian parable along the lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, with modern children as the central characters. She also produced retellings of Old Testament and New Testament stories.

Enid Blyton was a prolific author of short stories. These were first published, for the most part, in Sunny Stories, an Enid Blyton magazine, or other children's papers.

She also used to explore the forests when she was a little girl and wrote of her dreams in a notebook kept by her bedside.

Subject matter

Blyton's books often mirrored the fantasies of younger children. Children are free to play and explore without adult interference, more clearly than in most authors before or since — although the children in E. Nesbit's turn of the century works, and those in the Swallows and Amazons series (mostly 1930s) were equally independent. Adult characters are usually either authority figures (such as policemen, teachers, or parents) or adversaries to be conquered by the children. Children are self-sufficient, spending days away from home. This theme is taken to its extreme in two books: Five Run Away Together and The Secret Island: a group of children run away from unpleasant guardians to live on an island together, making a home and fending for themselves until their parents return.

Blyton's books are generally split into three types. One involves ordinary children in extraordinary situations, having adventures, solving crimes, or otherwise finding themselves in unusual circumstances. Examples include the Famous Five and Secret Seven, and the Adventure series.

The second and more conventional type is the boarding school story; the plots of these have more emphasis on the day-to-day life at school. This is the world of the midnight feast, the practical joke, and the social interaction of the various types of character. Examples of this type are the Malory Towers stories, the St Clare's series, and the Naughtiest Girl books and are typical of the times — many comics of the day, for instance, also contained similar types of story.

The third type is the fantastical. Children are typically transported into a magical world in which they meet fairies, goblins, elves, or other fantasy creatures. Examples of this type are the Wishing-Chair books and The Faraway Tree. Alternatively, in many of her short stories, toys are shown to come alive when humans are not around.

Controversies and revisions

Blyton's status as a bestselling author is in spite of disapproval of her works from various perspectives, which has led to altered reprints of the books and withdrawals or “bans” from libraries. In the 1990s, Chorion, the owners of Blyton's works, edited her books to remove passages that were deemed racist or sexist.[4] The children’s author Anne Fine presented an overview of the concerns about Blyton's work and responses to them on BBC Radio 4 in November 2008, in which she noted the “drip, drip, drip of disapproval” associated with the books.[5] [1]

"Blyton bans"

It was frequently reported (in the 1950s and also from the 1980s onwards) that various children's libraries removed some of Blyton's works from the shelves. The history of such "Blyton bans" is confused. Some librarians certainly at times felt that Blyton's restricted use of language, a conscious product of her teaching background, militated against appreciation of more literary qualities. There was some precedent in the treatment of L. Frank Baum's Oz books (and the many sequels by others) by librarians in the United States in the 1930s.

A careful account of anti-Blyton attacks is given in Chapter 4 of Robert Druce's This Day Our Daily Fictions. The British Journal of Education in 1955 carried a piece by Janice Dohn, an American children's librarian, considering Blyton's writing together with authors of formula fiction, and making negative comments about Blyton's devices and tone. A 1958 article in Encounter by Colin Welch, directed against the Noddy character, was reprinted in a New Zealand librarians' periodical. This gave rise to the first rumour of a New Zealand "library ban" on Blyton's books, a recurrent press canard. Policy on buying and stocking Blyton's books by British public libraries drew attention in newspaper reports from the early 1960s to the end of the 1970s, as local decisions were made by a London borough, Birmingham, Nottingham and other central libraries.

There is no evidence that her books' popularity ever suffered. She was defended by populist journalists, and others. Her response is said to be that she was not interested in the views of critics aged over 12.[6]

BBC bans

In November 2009 it was revealed in the British press that the BBC had a longstanding ban on dramatising Blyton's books on the radio from the 1930s to the 1950s. Letters and memos from the BBC Archive show that producers and executives at that time described Blyton as a "tenacious second-rater" who wrote "stilted and longwinded" books which were not suitable to be broadcast. In 1936 Blyton wrote to the BBC suggesting herself as a broadcaster, pointing out that she had "written probably more books than any other writer." She was turned down. In 1938, Blyton's husband, Hugh Pollock, wrote to Sir John Reith, the then Director General of the BBC, pointing out that his wife was getting letters from children from all parts of the British Empire, and that she should be allowed to speak to them via the radio. Jean E. Sutcliffe, of the BBC's schools broadcast department wrote, "Her stories...haven't much literary value. There is rather a lot of the Pink-winky-Doodle-doodle Dum-dumm type of name (and lots of pixies) in the original tales."[7][8]

Blyton tried to get her work on the radio again in 1940, but her manuscript was again turned down, the BBC employee who reviewed it writing, "This is really not good enough. Very little happens and the dialogue is so stilted and long-winded...It really is odd to think that this woman is a bestseller." Eventually, in 1954, Blyton's works appeared on air for the first time. Jean Sutcliffe at that time wrote of Blyton's ability to churn out "mediocre material" that "Her capacity to do so, amounts to genius...anyone else would have died of boredom long ago." Michael Rosen, the former Children's Laureate, said of the BBC's ban on Blyton, "...the quality of the writing itself was poor...it was felt that there was a lot of snobbery and racism in the writing...There is all sorts of stuff about oiks and lower orders."[7]

Dated attitudes and altered reprints

The books are very much of their time, particularly the titles published in the 1950s. They present the UK's class system — that is to say, "rough" versus "decent".[9] Many of Blyton's children's books similarly reflected negative stereotypes regarding gender, race, and class.

The most startling incidence of this type of material to a modern audience might be the use of a phrase like "black as a nigger with soot" appearing in Five Go off to Camp.[10][11] At the time, "Negro" was the standard formal term and "nigger" a relatively common colloquialism. This is one of the most obvious targets for alteration in modern reprints, along with the replacement of golliwogs with teddy bears or goblins. Some of these responses by publishers to contemporary attitudes on racial stereotypes has itself drawn criticism from those adults who view it as tampering with an important piece of the history of children's literature. The Druce book brings up the case of The Little Black Doll (who wanted to be pink), which was turned on its head in a reprint. Also removed in deference to modern ethical attitudes are many casual references to slaves and to corporal punishment. Blyton's attitudes came under criticism during her working lifetime; a publisher rejected a story of hers in 1960, taking a negative literary view of it but also saying that "There is a faint but unattractive touch of old-fashioned xenophobia in the author's attitude to the thieves; they are 'foreign'...and this seems to be regarded as sufficient to explain their criminality."[12]

Similarly, some have suggested the depictions of boys and girls in her books was sexist. For example, a 2005 Guardian article[13] suggested that the Famous Five depicts a power struggle between Julian, Dick and George (Georgina), with the female characters either acting like boys or being heavily put-upon. Although the issues are more subjective than with some of the racial issues, it has been suggested that a new edition of the book will "address" these issues through alterations, which has led to the expression of nostalgia for the books and their lack of political correctness.[14] In the Secret Seven books, the girls are deliberately excluded from tasks such as investigating the villains' hideouts — in Go Ahead, Secret Seven, it is directly stated "'Certainly not,' said Peter, sounding very grown-up all of a sudden. 'This is a man's job, exploring that coal-hole'".[15] In the Famous Five this is less often the case, but in Five on a Hike Together, Julian gives similar orders to George: "You may look like a boy and behave like a boy, but you're a girl all the same. And like it or not, girls have got to be taken care of."[16]

Film

The story of Blyton's life was turned into a BBC film in 2009 with Academy Award nominated actress Helena Bonham Carter in the title role. Filming began in March 2009 and first aired in the United Kingdom on BBC Four on 16 November 2009, followed by a former documentary on Enid Blyton. Bonham Carter starred alongside Matthew Macfadyen and Denis Lawson who played Blyton's first husband Hugh Pollock and Blyton's second husband Kenneth Darrell Waters respectively.[17]

Statistics

- Blyton's books have sold more than 600 million copies[18]

- More than a million Famous Five books are sold worldwide each year

- Her books have been translated into more than 90 different languages

- The Magic Faraway Tree was voted no. 66 in the BBC's Big Read.

- In the 2008 Costa Book Awards, Enid Blyton was voted the best-loved author, ahead of Roald Dahl, JK Rowling and Shakespeare[19][20]

- 753 titles credited to her over a 45 year career with an average of 16 titles published per year

See also

- Enid Blyton Society

- Enid Blyton's illustrators

References

- ↑ "Index Translationum Statistics". Index Translationum. UNESCO. http://databases.unesco.org/xtrans/stat/xTransStat.a?VL1=A&top=50&lg=0. Retrieved 2007-07-12. This index contains titles in all the translated languages. The top five are: Walt Disney Productions, Agatha Christie, Jules Verne, Shakespeare, Enid Blyton, and the next five: Vladimir Lenin, Barbara Cartland, Danielle Steel, Hans Christian Andersen, and Stephen King

- ↑ Ray, Sheila (October 2005). "Blyton , Enid Mary (1897–1968)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/31939. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- ↑ Gyles Brandreth (2002-03-31). "Unhappy Families". The Age (Melbourne). http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2002/03/30/1017206160031.html.

- ↑ Geoghegan, Tom, The mystery of Enid Blyton's revival, BBC News Magazine, 5 September 2008

- ↑ Fine, Anne, A Fine Defence of Enid Blyton, BBC Radio 4, 2008

- ↑ The Mystery of Enid Blyton

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Will Pavia in The Times 16 November 2009

- ↑ News.BBC.co.uk 'Small beer' Blyton banned by BBC BBC News, 15 November 2009

- ↑ Druce () "The system of middle-class values (and of automatic value-judgements entailed by such a system) which Blyton presents is simple enough." (p. 222) "In Blyton, an indifference to dirt, grease, foul smells and untidiness is a defining characteristic of the working class." (p. 225)

- ↑ Bibsbooks.co.uk

- ↑ EndidBlyton.net

- ↑ When Blyton fell out of the good books - smh.com.au

- ↑ "The Famous Five - in their own words", Lucy Mangan, The Guardian, 22 December 2005 Guardian.co.uk

- ↑ Row faster, George! The PC meddlers are chasing us! - Daily Mail

- ↑ Blyton, Enid; Go Ahead, Secret Seven; Knight Books;(1953)

- ↑ Enid Blyton - Five On a Hike Together

- ↑ Digital Spy: BBC producing Enid Blyton film

- ↑ ABD.net.au

- ↑ News.BBC.co.uk

- ↑ CostaBookAwards.com

Further reading

- Enid Blyton (1952) The Story of My Life

- Barbara Stoney (1974) Enid Blyton, 1992 The Enid Blyton Biography, Hodder, London ISBN 0-340-58348-7 (paperback) ISBN 0-340-16514-6

- Mason Willey (1993) Enid Blyton: A Bibliography of First Editions and Other Collectible Books ISBN 0-9521284-0-3

- S. G. Ray (1982) The Blyton Phenomenon

- Bob Mullan (1987) The Enid Blyton Story

- George Greenfield (1998) Enid Blyton

- Robert Druce (1992) This Day Our Daily Fictions: An Enquiry into the Multi-Million Bestseller Status of Enid Blyton and Ian Fleming

External links

- Watch & Listen to BBC archive programmes about Enid Blyton

- Enid Blyton letters from the BBC archive

- Enid Blyton Society

- Enid Blyton Net

- Golliwogg.co.uk - an independent guide to Golliwogs - "Golliwogs & Racism"

- Enid Blyton en español (Spanish)

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||